Interview with Prawta Annez

by Francesco Giannotta & Szymon Kwinto

Prawta Annez is an amazing artist and person with talent and passion that radiates and could make for its own infectious disease. (Don’t worry, it's not deadly) For the record, we met Prawta at University, where we both had the pleasure of working for her film “Towels”. Her style of directing was inspiring and seemed to come naturally to her. She was never authoritarian with her direction but was also clear with her vision and not afraid to speak her mind. Our interview started with intentions of clinical professionalism however quickly it became a conversation between friends who haven’t spoken in over a year.

Prawta currently tirelessly works as a professional storyboard artist and occasionally posts personal art pieces on her instagram page. We were overjoyed to talk with her and learn about how she uses social media as her art journal and how she creates these pieces with strong personal messages behind them. We strongly recommend watching her film “Towels” and following her artwork on her social media.

Be it a film, a doodle, an illustration, an animation, or whatever she decides to work on, you’ll come to understand by reading this interview what an uncompromising force of nature she is and why she is an artist worth keeping an eye on.

F: Obviously, because I am exceptionally selfish, I want to begin by talking about Towels. You know, it’s one of those things, I worked on it and I’m proud that I worked on it and you directed it.

P: Can you believe that more 43.4k people have viewed it?!

F: That’s amazing! I was on Facebook the other day and I saw an Italian page I follow that posted this article about you and your film, it was so exciting. It made me feel so proud!

P: It’s so surreal though! I remember freaking out about the project so many times. I kept thinking, “Is it going to finish, am I going to survive this mentally, is my crew going to stay with me?”. It’s really nice that all of us cuddled up in that weird cold room (the animation studio at our university) and eventually it ended up well.

F: Yeah, and that’s something I wanted to talk to you about as well: how has it changed in your eyes. I know that there is something to be said about the perceived meaning of the film that has shifted, especially this year – which is kind of fantastic to witness in its own right. Your original meaning was somewhat related to this, but you could have never imagined it would have become so relevant.

P: It was a reflection of a particular political situation at the time, but the message still seems to carry through no matter what decade we’re in as we still have the same personal and political problems that are still at the core of the film. But how the film now feels like it’s also about social distancing is quite funny as well!

F: How did you feel about this shift in meaning?

P: I like it! I really do. I think it means that I’ve done something right because I made something that allows people to reflect their ideas upon. You know, back in university, some of our lecturers said that all art has to have a meaning, and I agree that you should know your film and what you want to say enough to get it done – but for me the whole purpose of art is to be able to touch people in their own different ways and allow a people to think for themselves. Some artists prefer to have their message loud and clear and that’s fine, but I think that allowing interpretation is part of the beauty of creating something.

A couple of film festivals and some people have reached out to Camilla (producer of Towels) and I about Towels since it’s been out and they’ve all picked up on the core message of it. However, what situation they relate it to and how differently they’ve interpreted the smaller elements, especially which characters they like and don’t like, is really interesting.

Some people hate the main guy, while some people really relate to him.

"Since I was in school, I developed a very strong attachment to my gut feeling. I definitely believe in going with your gut."

F: You posted it online during the self-isolation phase of the world. Was that accidental?

P: No [laughs]. Well actually yes it was, and also no it wasn’t. Camilla and I were very, very strict about wanting to release it in summer. It had to be released during a hot time of the year because it’s set on the beach and it just felt like the perfect time to release it – not when people are cold inside. If you watch the trailer though, it says “Coming in 2018”. [laughs] So… yeah we definitely didn’t think it would be delayed two years – but it was a strange and happy coincidence that it actually worked out better for the film.

F: I think so too, it has that quality because Towels has that isolation theme that just works perfectly for the situation.

P: Yeah [laughs]. It’s a lot of sheer dumb luck, it worked quite well. The only reason it got delayed two years is because Camilla and I were so busy after graduation that we didn’t have time to focus on it.

F: Reception to the film has been great, and everyone seems to have loved it – which is to be expected…

P: You know what I’m really curious about? I strangely really want someone to tell us what they don’t like about the film [laughs]. A part of me really wants someone to message us and say, “I saw this thing and it made me feel this and I disagree with that” – not that I am calling out for them, but I am really curious. I don’t know if it’s my sadistic artistic side that just craves criticism.

F: Did you ever worry about the film being misinterpreted when you released it? Or did you hope for it? [laughs]

P: I personally don't really want it to be misinterpreted because it’s still my personal feelings about a certain political time and I didn’t want someone to come up to me and say “oh who’s side are you on”. That would have made me feel like all of it was for nothing. But a part of me doesn’t really want to take it personally either.

If I went with the original idea for the film, I think the controversial response would have probably been a lot harsher, because I wanted to basically include a caricature of Trump turning up right at the end. [laughs] But our lecturers told me to try to appeal to a wider international audience. Although there is a part of me that almost wishes I just did it, I do like how UK, and European and international audiences can identify with the version I went with and that it wasn’t limited to the American political situation.

"...if you just let go of all that and allow yourself to simply paint freely, most of the time I find your ideas tend to form a lot freer and faster."

F: I guess it’s also a political feeling that many people around the world are feeling right now, sadly.

P: Yes, indeed. I do find it interesting that the film was made at the beginning of Trump’s inauguration and now it’s been released in the final year of his first term – whether he gets re-elected or not (n.b. this interview was conducted shortly before the 2020 U.S. elections.).

F: It all just keeps adding layer after layer to the meaning of the film. When it was made it was a reaction to what was going to happen (after Trump's inauguration), and now four years later, a lot happened and it’s still the same.

S: You mentioned that a lot of people really related to the film. Did you ever ask these people about their political opinion? Do you think that had an influence on which character they liked or didn’t?

P: Camilla and I have never actually asked, and people haven’t told us their political views. I think it’s just one of those things that are hard to get out of people. But it would be interesting to know where their viewpoint comes from.

S: I think, just to add to the greatness of your film – the way you mention you kept it open is what truly makes it remarkable, that it’s so open despite having a clear idea and message.

P: We purposefully kept the imagery very simplistic. The characters aren’t strictly male or female, the beach is just a beach with no distinguishable landmarks, everything is a simple clean palette to work off. That was intentional, to keep everything almost as general and anonymous as possible.

S: Do you think that could be taken too far sometimes?

P: I sometimes feel like it can but that’s my own personal taste. Some artists prefer extremely graphic and minimalistic qualities, while some artists don’t. I personally feel like if it is too minimalistic and anonymous sometimes it almost removes too much. Saying that though I actually really enjoy abstract art so who am I to say.

S: Yeah, you don’t want the sanitary aspect of the film, you want there to be an opinion. You want it to be able to be open to interpretation on some level.

P: Actually, talking about symbolism and interpretations – I just remembered that the one main thing I was a bit unsure about in terms of what people would interpret is the hole. When the hole opens in the middle of his body while he’s looking at his fist. My personal interpretation is that the hole is like the emptiness inside of him, the guilt, the badness, after he resorts to violence in the end or the punch. Basically like how after you’ve done something bad there can be that hollow feeling inside – whether you think what you did is bad or not you just instinctively know there’s something inherently wrong.

That’s what I interpret from the hole, but even when the film was going through the animatic reviews (n.b. in university we would review the films weekly with our lecturers) the lecturers themselves were divided about what the hole represented. So, I was a bit unsure about how it would be received. Someone said it could be interpreted in a “Freudian” way or in a sexual manner [laughs], someone said it was his fear, and someone interpreted it very logically, like he had to go find something to fill that hole. Some people even felt it was a bit random that the hole appeared, like it shouldn’t even be included in the film.

I do think I could have done the film without the hole appearing and the message would have still come across, but I personally felt the hole visually captured what it feels to be empty and guilty.

S: Obviously whilst we can, in hindsight, think that anyone who saw an early version of the film and commented on it might be kind of ridiculous, on the spot it’s a lot of pressure and fear to be misrepresented. How do you deal with that feeling?

P: To be honest, I think it’s one of my strengths. Since I was in school, I developed a very strong attachment to my gut feeling. I definitely believe in going with your gut. In my personal life I’ve had to make a lot of decisions myself without parental or adult advice just because of how my home situation was at the time and currently is. So I’ve had to rely on my own instincts quite heavily from a young age. I definitely went through that phase in my teenage years when the art teacher criticizes your art and your pride gets hurt and you take everything extremely personally, but I think I overcame that relatively quickly largely because of that gut instinct. I learnt to discern the sensible advice from what needs to be defied. I see it almost like a voting panel, or people giving me pieces of information: I can sort through it almost with a slight detachment of emotion and then decide what’s useful and what’s not.

S: I think that shows. And I think what I learned by working on your production and seeing your film develop from early on to the final film helped strengthen my argument with myself and with the other people that were working on Bug Bombed. We needed to have a strength within ourselves to listen to some advice and to ignore stuff that we believed was wrong.

P: Do you remember the earlier meetings of Towels? I said things that were almost a pep talk to myself as well. I said that “I want this project to be fun, I want us to make mistakes” and having that mood already set, the attitude was perfect. It didn’t have to be perfect or the best film, but it had to be a project where I got to experiment, I got to make mistakes, and not worry too hard about ensuring all the meanings come across and also, to release a bit of ownership to allow me to approach it more freely.

You know when you’re painting and sometimes you get too precious about what gets on the canvas and you get stuck because it’s not going how you want, or that one colour is not actually working – but if you just let go of all that and allow yourself to simply paint freely, most of the time I find your ideas tend to form a lot freer and faster. And a lot of the times a lot better too!

I kind of went with that mindset for making the film.

S: I kind of went the opposite with our production [laughs], I ruled with an iron fist.

P: [laughs] But I think with your film it was more specific. You had a lot of dialogue and a lot more story to tackle.

S: I wouldn’t say more story, but I think the strength of your film was the fact that you had the ability with the style to really just kind of let people be experimental. I think your production went well also because you were very quick to say what worked and what didn’t work. And you wouldn’t bullshit us, which was a thing that I really enjoyed. Like, if I made a test or something like that and I thought it was great, you would come and you would tell me if it didn’t work regardless, and I think everybody got that and that was why everybody respected you and continued to work with you.

F: I want to add, I had the best time working with you because of this reason, because of how quick…

P: Wait wait wait no, the feeling is completely mutual! I worked on five projects now and Towels is still the most enjoyable crew I’ve ever worked with. It was so easy that it actually misled me a bit about what it’s like working in the industry!

F: I think your quickness and your attitude towards making this film how you wanted it, while also allowing your crew to make mistakes and helping us fixing them on the spot and being quick and being open was key to the success that Towels got back then and is still getting right now. I always brag about it with my friends.

P: I’m so happy to hear that!

F: And to add to what you said about Bug Bombed, I think the big difference is also that comedy needs to be way more precise.

P: My biggest weakness is actually comedy I think, even with boarding and writing it’s the hardest thing for me. Humour is so vast and to be able to sell your humour to other people is like a superpower. Comedy scares me so much!

S: I think Fran and I both agree here that you fit the role of director pretty quickly and pretty well. Where do you think that comes from, and what moulded you to do that, and do you think it’s something that came naturally or that can be learned?

P: I think it was sheer desperation to be honest! [laughs] Because if someone came to me today and asked me if I wanted to direct a children series of a mainstream animated feature, I probably would say in the politest of ways possible, “no, thank you”.

I just think I was so desperate to have a third year project that was experimental. If you remember, most of the pitches from my year group were 2D films and 3D films that reflected or looked similar to the current mainstream animation industry – but I was itching to work on something different. I was actually waiting for someone to pitch an experimental film to work on and was eager to become a crew member, but no one did. So that’s why I decided to pitch my film. I didn’t even think it was going to get through.

S: I think the funny thing with the pitches is that in your year it was a reflection of the I Am Dyslexic [n.b. a successful short film produced the year prior Prawta’s film] phase beforehand and then. I don’t know if you realised, but after you left (university), everybody was expected to pitch an experimental film – so we actually had to deal with your aftermath [laughs].

P: Honestly nothing makes me cringe inside more than how they put us on such a pedestal afterwards and put a lot of expectations on us. If I come to the studio my name and the word Towels come up and the students give me a look like “oh *that* film”.

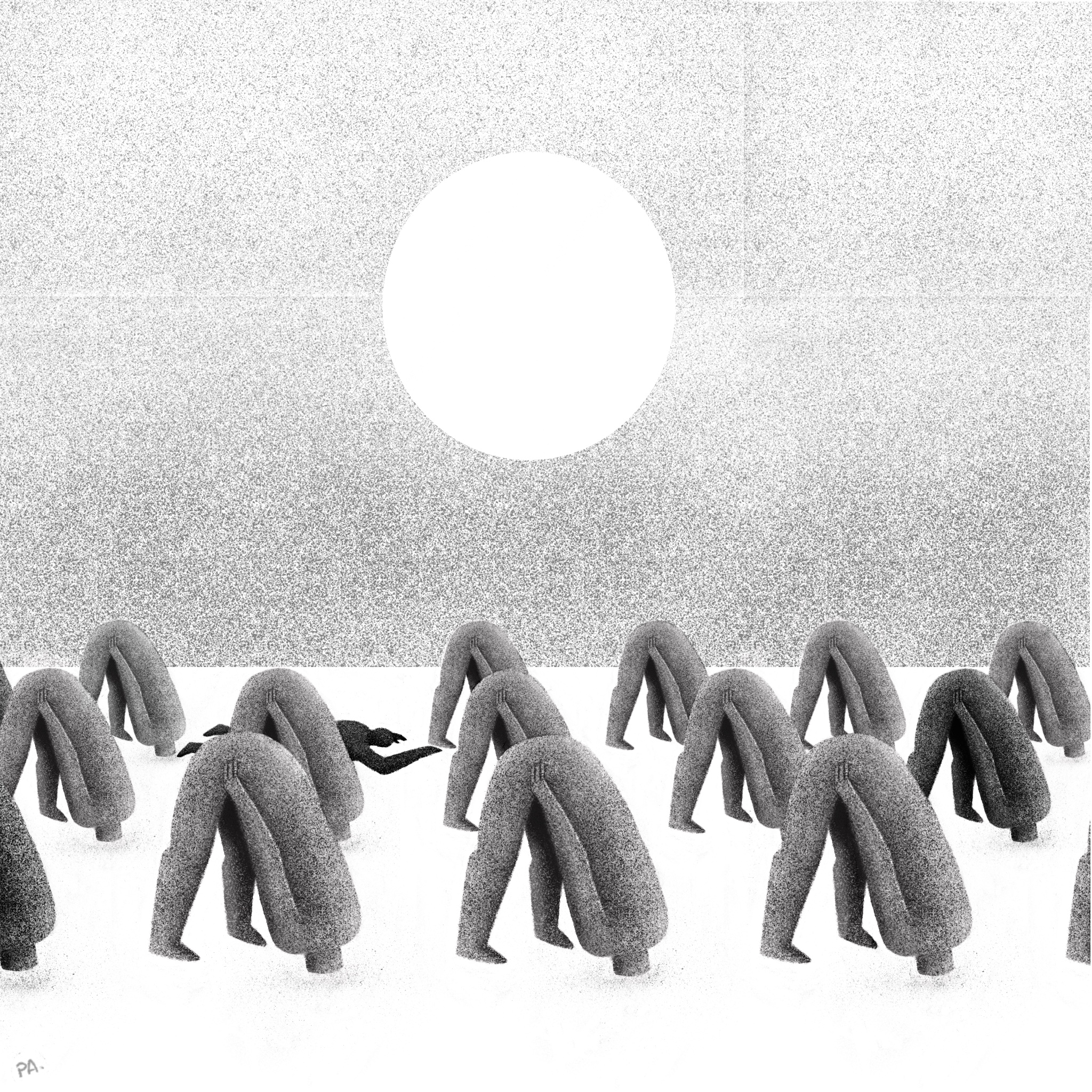

S: I want to ask you about your creative process. I think, correct me if I’m wrong, that all the work you produced has some sort of meaning to it. It always feels like there is a layer of solid subtext under every piece I see, even though sometimes I may not understand it immediately. Do you start out with a meaning in your head that you project or is it created as you go along while creating the work?

P: I think you guys know I am mildly dyslexic, and I was slow to learn to read or write properly for my age. I was in the ‘English as a Second Language’ classes even though English was technically my first language. I was even taken to see a learning specialists because my dad was all like, “everyone in the family is a genius why aren’t you reading yet”. My family was also one of those that didn’t have TV in the house either. We would watch movies either by buying CD’s or going to the cinema, but we were heavily about books so there were words everywhere – and for me it was a massive wall, and behind this wall was a beautiful garden of stories and worlds created by words that I couldn’t reach, so the way I would respond to it – because I couldn’t really write down things verbally – was that I instinctively started to draw. A lot! I would do that because I had so many emotions and stories that I couldn’t communicate through with words. So I vented out on drawings at a very young age and that stuck with me.

So even now, when I’m drawing something, I don’t think about what I’m communicating analytically but I draw what I’m feeling on that day and it seeps into it.

F: So you would say your drawings have a lot to do with instincts. You’re very emotional when you draw.

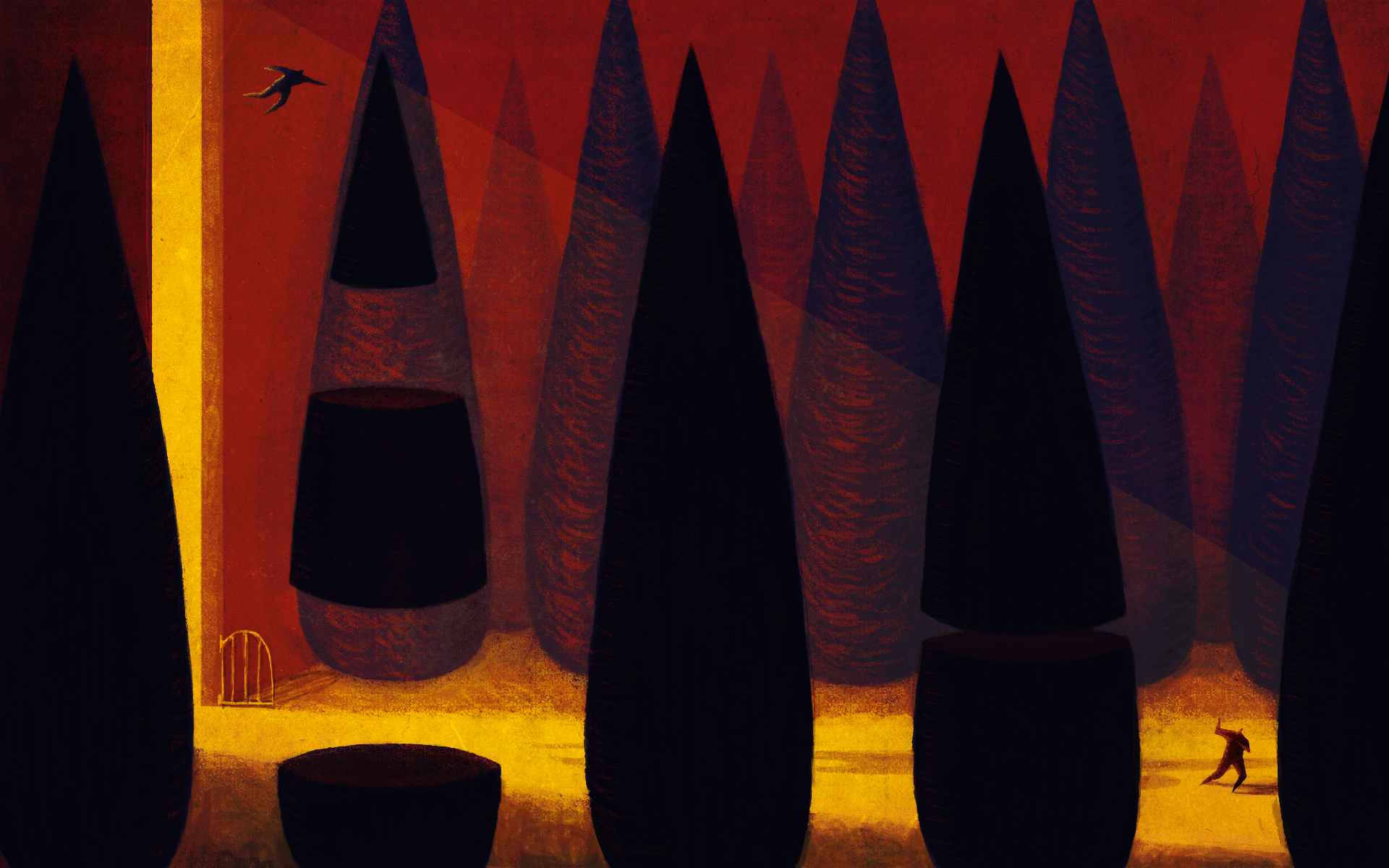

P: Yes, especially when I’m watching something or listening to something, and it feeds quite directly into it. So, if I’m watching a Spanish film in the background, without realizing it, my drawings will end up having influences of Spanish artists that I’ve seen in the past or Spanish settings. Or if it’s a political thing in the background I’ll draw something that maybe is a bit more angsty, with a political subtext – so yeah, the funny thing is if I try to go in with a plan most of the time the artwork never really turns out quite right.

S: Would it be fair to say that you use your artwork almost in a therapeutic way?

P: Yeah, very much so. Which is why I’m grateful that the work I do for a living [n.b. storyboarding] is nothing really like the work I do personally. Because I feel if I had to do what I do personally for a living it would corrupt that intimate feeling and that process that I have with drawing.

S: Because you do this kind of therapeutic work, do you feel worried or nervous about putting it out there because it’s so personal?

P: Is it “act before you think”? I have a habit of doing that. Sometimes my mouth and my actions jump before I can assess them, so I think most of the time when I put things out I do it before I even think about it. Also I feel like my work is weird enough that the meaning is so deeply embedded there in the image that I don’t feel too vulnerable. I tend find myself drawn to visuals that are rather surreal, with weird creatures, weird settings, most of my work doesn’t tend to be completely humanoid, and also the settings don’t really tend to be a specific city or a landmark, and I think that’s why I feel comfortable with it, because it’s like a fantasy world I created to hide my feelings and thoughts away in.

So it is very intimate, but probably feels more obvious to me what the full meaning or story is than it appears to other people.

S: Detached, almost.

P: Yeah, disguised.

"I definitely have two artists inside me. One is the artist that I reserve for professional work, and the other one that I keep aside for personal work – that is the true Prawta and then there is the professional Prawta, the Prawta in the suit."

S: It’s good that you have that quality for your work of not holding back and going, “I’ll do it” and see what happens. It almost stops that ‘barrier’ forming.

P: It’s definitely both a good thing and a bad thing. I think what I struggle with is communicating my methods with others and translating it over. So, if I do something personally and someone’s like, “how can I replicate this? Or how can I do something similar? Or can you teach this to me?”, I struggle to explain it because it’s not like I make a sketch before every piece. In fact, I tend to begin with just a blob on the paper. I don’t really know how to break it down and sometimes I struggle with figuring it out myself, so if one day I want to work on a short film using my style I’m going to have to really sit down and break down my artwork.

S: Would you say you prefer working alone or with a team, and why? And does it depend on the type of work you’re doing?

P: It depends on what I’m trying to create. I definitely enjoy the more traditional side of art and that kind of style. If I’m trying to explore my personal work or different styles, I like doing that privately – almost like a social recluse type of ‘alone’. I’ll lock myself in a room – a very stereotypical tortured artist kind of situation. And I really love it, I love alone time where I could just deep dive and play. I’ve tried to do that in a shared studio space before and it tends to almost restrict my natural flow because I tend to be really self-conscious about people looking at me, wanting to see my work half finished. It’s a lot of pressure.

But when it comes to creating something bigger that’s not just a single image, I love working with other people. I especially enjoy working with a small crew of people who are different and have different backgrounds. Maybe with a similar interest, a similar appreciation for a style or an art movement to connect with each other and the film but still have the other interests or specialties that they have in life that are very different and can be brought to the table to make the film even better. So maybe a crew of people who enjoy postmodernism but one of them has a background in biology, or someone who makes music or also works as an engineer. Basically a variety of people with a common heartstring.

But for the larger crews typically found in industry, with teams of 30+ people, I think I would prefer being a groundworker for big groups like that. I think I prefer to be a part of the crew in a large production. I don’t think I would really be able to manage a larger team and project like that.

S: I think it shows why in general we enjoyed working with you, that you wanted different people’s opinions but you knew how to stir it. You were selective but also knew what you were looking for.

P: I do really believe in working to your strengths. If, for example, you have a crew of five people and one of them cannot for the sake of their life do oil painting, but they’re really, really good at watercolour paintings, I’d be like, “Screw it! You don’t have to do oil painting even though this project is oil painting, but why don’t you do some watercolour experiments and we’ll see if it fits it and might even improve this project”.

I think there are two different groups of artists: the ones that if they make a mistake they erase it because they are following a very specific image that they want to create; and the other type of artists that, if they make a mistake during the process, are like “fuck it, I'mma just go with it” and just embrace the mistake as part of their work. I’m definitely the latter. Which is why since I was 12 or 13 I stopped drawing with pencil – I used to try and try and sketch with pencils but then when I got to that age I said “screw it!”. I hated the marks that erasers make so I removed all the pencils from my pencil case and stuck mainly to ballpoint pens and ink, which ended up influencing my artwork and style from then on. That’s really the kind of the mindset that I work with.

S: Do you get artist block? How do you handle it?

P: I definitely have two artists inside me. One is the artist that I reserve for professional work, and the other one that I keep aside for personal work – that is the true Prawta and then there is the professional Prawta, the Prawta in the suit.

I think the Prawta in the suit really struggles with art block because if it’s not something personal, something that comes from instinct, then I struggle a lot because it’s not something I can immediately identify. If I’m working on a 3D kids series with a cute cartoon with huge eyes and I have to board a scene and make it look awesome, sometimes I just find myself stumped because I might not really understand the sense of humour or something like that but I still have to make it work, and I’ll get stuck. But when it happens I’ll usually just go back to the pitch bible or the mood-board of that series and I’ll binge watch whatever film or show they are inspired by and that inspiration usually gets me out of professional blocks. I look over the pitch bible as often as possible and I’ll draw a couple of panels of similar shows to get myself in the right mindset.

However with my personal work and art block, I tend to experience it completely differently. My sister really hates me when I say this because she hates the idea of the tortured artist, but I find when I’m really happy and life is really going my way I tend to have nothing to draw and when I do it tends to be kind of dull in a way. But when I’m feeling really shit or frustrated and I can’t communicate my emotions in my current situation, then I can produce work without even thinking about it. All I have to do is just sit down with a blank piece of something in front me, whether it’s a digital canvas or even a notepad, turn on some music, and just go into – you know when you stare at something and unfocus your eyes a bit? That feeling when you daydream?

That’s kind of what I go into.

I put a movie on that I don’t really have to focus on, I put some music on, or a podcast and I’ll go in that day dream like state and just start drawing. And most of the time my body will just start pouring stuff out and weird shit will just start appearing on my page. So, I don’t tend to experience as much art block with my personal stuff because I can turn to that method quite reliably. Because even if I have no real idea of what to draw, I just basically sit down, relax, try not to think about drawing and just doodle, and then my doodles tend to become finished pieces. So, one side has definitely more of a problem than the other, with my personal work I know how to almost coax it out.

As for 2020, I think it has been great for my personal work but terrible for my professional work. I’ve been able to reach deadlines but if I’m bored during the day it’s really hard to force myself to draw, especially if this is very different to my natural style, or maybe that particular scene is a little boring to me at the moment– but that’s just the life of a storyboard artist. You just kind of have to find something about it that draws you back in or just power through it because at the end of the day you have a deadline to meet.

As for my personal work – I just had so much angst and I was stuck in a cave that is my house, so my mind has almost enjoyed the madness quite a bit. A lot of visual venting for me in 2020.

"I think a lot of people of colour feel this pressure of, “everything I do needs to speak up or do something right”. There’s an expectation put on yourself to almost be the voice of those who don’t have a voice kind of thing, and that definitely puts on a lot of pressure."

S: That further pushes the idea that you use your work almost in a therapeutic way. But I have a question about that – obviously you mentioned that you don’t want to be in charge in a big project, and that there is that separation between personal and professional work, is that because you fear that if you got steady work or if you started doing really, really well as a fine artist that it would be difficult to continue that state of “tortured artist” in order to produce good work?

P: I don’t know to be honest, because I’ve never experienced it yet. I think the impostor syndrome inside of me tells me I never will, and I don’t deserve to fully enjoy and do my personal work 24/7 – so I think the fear in me tells me “no no no no if you ever get to do that, you’ll hate it, it’ll be horrible”, but who knows! At the end of the day if you get to do what you love 24/7 and you get to be as mad as you want, and people love your work I’m sure you’d love it.

Realistically, if I got paid a lot of money to do all my random doodles, I would probably be super happy.

S: Are your family and friends supportive of what you do? How does that affect your work? To bring it back to myself for a moment, I find that my parents are very supportive and some of my friends are very supportive but obviously they know I do really weird stuff, so they love what I’m doing but they don’t always know what it is [laughs].

P: I know exactly what you mean! I have maybe five or less friends who truly understand my work. Sometimes you find people who understand your work better than you understand it yourself. One of those people for me is my sister and we are – as my boyfriend likes to say – abnormally close. We have a two-year age gap, we’re completely different physically and emotionally, but we’re a lot like twins. Because of the things we’ve experienced through life, losing my dad, living together in a house that’s not our family’s house, going to boarding school together, we were almost forced to become completely reliant on each other. We went from fighting like cats and dogs all the time to having separation anxiety when we are apart.

There are also a lot of friends out there who do appreciate my work but might not really get it, “yeah she does weird shit and draws naked people” [laughs] “there’s probably going to be a boob somewhere”.

In terms of family, I have a very strange family dynamic. I come from a core family of hippie parents, I guess. Even though my dad worked at a law firm, was a part-time lecturer and an owner of a software company, and my mom was a teacher, both of them had a high appreciation of the arts and very much didn’t believe in grades, but believed in putting your 100% in so it didn’t matter if you got a D as long as you did your best. They believed that at the end of the day if you got a D but deep down you knew you worked your ass off for it, BE proud of it. But at the same time if you got a B but you knew deep down that you didn’t give it your all, you’ll know that you let yourself down. So, they encouraged a lot of self-growth and self-assessment at a young age.

But after my dad passed away, my family became a little bit estranged and my sister has always been the academic star in our family, so she’s had to deal with the whole family spotlight being on her – and it’s a win and lose situation. My sister has all the attention on her, but with that she has to deal with a lot of pressure from the family to succeed, she has to do with a lot of people having input on what to do with her life, while me on the other hand – I grew up from a young age with people thinking “oh she’s the artist in the family” and no one really following what I do. I almost got to sneak away in the shadows and that’s worked out quite well for me because it’s meant that I’ve had to rely a lot on my own decisions. I did a lot of things by myself because no one was really paying attention as much, but at the same time it allowed me to follow the path I truly wanted.

There’s been a mixture of support. They’re there for me but they don’t really understand what I do. Which is sad but it being so has helped me become the artist I am today; it's good and bad.

"If you guys saw me draw something happy would you think it was normal?"

S: It explains the drive that you have, and I think everybody who has worked with you or around you feels that. Thanks for answering the question. Does the fact that the people around you not really understand your artworks drive you to maybe make something more palatable for them?

P: I think they gave up on me a while ago [laughs]. My uncle, I think I was 14 then, went to one of my school art exhibition things and after my teacher praised my work, he went over and most of my work was really dark, like people tearing flesh, naked bodies burning, girls crying–imagine teenage Prawta with her teenage angstI, it was perfect for releasing all my emotion on the canvas, but outside I was still a cheerful, talkative, bubbly kid.

So my uncle turned to me and I remember him asking me, “Do you ever draw anything happy? Are you okay?” and I was happy! I didn’t have any dark thoughts. I mean I naturally had my own personal issues, but it wasn’t exactly, “I hate life! I hate society” – I was just ‘angsty’.

If I drew something dark or a horrific scene, my friends at the time would just say “oh that’s Prawta, whatever”. But if I happen to draw something happy, a lot of them would ask me if it’s even my work.

F: “Are you okay?!”

P: [laughs] If you guys saw me draw something happy would you think it was normal?

F: I would check up on you.

P: [laughs] This might be a bit TMI [n.b. Too Much Information] but I love this fact, it amuses me so much. When I was younger and going through puberty, I used to use my doodles as a gauge of when my period would start [laugh]. The darker my doodles got, the closer I was to starting my period – it was like clockwork! If you look at some of my high school sketchbooks, it was like my monthly cycle was reflected on the pages. That made me a bit fascinated with the psychology behind art. It’s really interesting to see how I did this subconsciously, I couldn’t hide it or fool myself trying to draw things differently. It’s a chemical/biological thing that happened but it clearly wasn’t withdrawn from my work, and it was all there – my whole self was laid bare.

S: I think that’s how some of your family handled it: “Hey Prawta is doing really dark stuff, don’t engage.”

P: Seriously! Loads of my family members were like, “Why is her artwork so dark!?”. You know how you have the core member of your family, and then the distant cousins, the aunts and stuff – I don’t know if you guys had this, but when you’re known as the artsy one in the family someone will contact you or approach you at someone’s wedding and ask you to do a piece for them. But then when they realise what kind of work you do, they’re like, “Oh… maybe not” [laughs].

S: I had the opposite! Because my whole family is made up of artists, there was a big pressure when I started doing art – obviously they were very supportive but there was a big joke, and that is “Why couldn’t you become a lawyer so we could have money for once?!”. And with the grades it was the same as you apart from anything art related. You got a C in maths? That’s fine. Art? C+? IN ART? No, you NEED an A!

P: That’s so funny, I can’t imagine what that’s like! That’s a lot of pressure. I don’t know if I would have thrived there. For me everyone was academic, and they understood and appreciated art, but they didn’t know the process behind or what it was like to create those pieces so they left me to it.

S: That’s why it’s interesting to hear your side, for me it’s more of, “I can draw, I can do this stuff because my family does that!”

P: The perfect way to describe my position and my family in your situation is that kind of weird frustration and isolation is like if you grew up with your artist family, but you couldn’t draw for shit, and the only thing you could do was write. That’s how it kind of felt growing up!

"With 2020, it definitely made me realise that no matter how big of a hero complex you have, or how much you want to be the saviour of the world, it is so fucking hard. It’s so hard to create work that will end up doing well and also to create work that in the real world will not offend people. Because at the end of the day there are so many different opinions out there, and your opinion isn’t always the correct one."

S: I have one last question (n.b. this “last question” is asked two pages before the end of this interview). Has 2020 changed the outlook of what you were planning to do with your career? Not just your professional work, but also your personal one?

P: I think it was one of the early lectures in university, I think Ann [n.b. one of our lecturers] was talking about symbolism and how what you create has a lot of power and you can’t just create things willy nilly because you don’t know whether your image or your artwork will be used for bad or for good. Even if it’s a small stickman, it can hold some sort of power. Even if you think your art means nothing, someone else could decide to use it in a different way, so back then I decided that whenever I made something I had to give it some sort of good purpose. And of course, that’s always impossible in the real world but I definitely had that hero complex where I wanted to make sure that my work had at least to fight for something. It couldn’t be about just… a dog for example.

With 2020, it definitely made me realise that no matter how big of a hero complex you have, or how much you want to be the saviour of the world, it is so fucking hard. It’s so hard to create work that will end up doing well and also to create work that in the real world will not offend people. Because at the end of the day there are so many different opinions out there, and your opinion isn’t always the correct one. The world is never as black and white as it may seem. And then there’s also the whole situation of white studios or white companies creating and telling stories for/about indigenous people or people of colour, like speaking for minorities instead of giving them the opportunity to tell their stories themselves– it’s a big thing I think about quite a lot. Because if I make another short or piece of art, do I want it to be about the part of me that is a minority , and try and lean further away from a more western and European narrative (Prawta is half-Thai, half Belgian)?

Should I try to highlight and create more information about my Asian side or my Thai ancestry? And like – I think a lot of people of colour feel this pressure of, “everything I do needs to speak up or do something right”. There’s an expectation put on yourself to almost be the voice of those who don’t have a voice kind of thing, and that definitely puts on a lot of pressure.

It would be so nice to just create anything for the shits and giggles of it, and I think there needs to be an element of that. I need to still have that play, that room for enjoyment and making mistakes, but it’s hard to balance that with wanting to do something meaningful and right, especially in 2020 and especially in the current climate and situation. It feels very doomsday-ish and you want to be that person who leaves the world a better place than how they found it.

At the end of the day I’m 24 going on 25 ,still figuring myself out, one person in a freaking huge world – if I try to recycle and eat less meat it’s still one person. At the end of the day I definitely had to learn to keep my ego in check and to think realistically that, sure, I can produce artwork that has meaning or is trying to do some good but I can’t put the pressure on the work – like, “This artwork is going to save the day! It’s going to appear on National Geographic and win awards and end all wars''. That’s probably the biggest struggle of 2020 for me. Where do I belong? Where do I fit in? How can I be of use yet not lose my passion?

"It’s like, “this is my voice, this is my art journal”, and yes maybe public people can come and look at it and reach out to me, but it’s still me putting my piece out there in the void."

S: I think that it’s interesting that I don’t really think that way because of my privilege. With my work I kind of make it and never really thought of it that way – I think that must be a lot of pressure to feel that burden. You understand ultimately that you can’t control whether somebody crazy is going to come and take your beloved logo or piece and make it into a war machine thing. That’s a very interesting perspective that I didn’t know about you. And I think it explains a lot about your work, and I’m the complete opposite. With that I’m like “I’m going to let the people determine what’s up with that” and if it becomes the face of destruction it’s kinda funny to me.

P: Like you said, in your work there’s a core of comedy – I guess you’re attracted to comedy as a form of getting through things sometimes.

S: To be honest I’m attracted to the theory of nihilism, I’m very nihilistic and I try to be an optimistic nihilist but I am often the complete opposite. But I have another question. Do you think social media has changed your work? Especially now, I tried to remove social media apps from my phone because all the opinions and all the noise really made me anxious and depressed.

How has it affected you? Maybe it hasn’t, maybe you love it?

P: I’ve had so many moments just like you when I’m like, “screw this” and I want to delete all social media and become a hermit. Like, screw this, there’s so many freaking artists out there, so much good and bad news, good and bad artists, but it’s also so many talented people that make you think, “Why do I even matter, why do I even try?” It feels like you’re running a marathon but everyone is ahead of you and then you can’t even see them anymore and you suddenly think, “Why do I even keep running?”

I’ve even deleted the app off my phone a couple of times, but then re-downloaded it. At the end of the day I think I keep going back to Instagram because I think of how I used it at the beginning. When I started, I didn’t use it as a way of displaying my work but used it more as an art journal. So, if I want to keep it, I need to remember that at the end of the day it’s a place to express myself. I made it public so that maybe people who have seen ‘Towels’ and looked me up can have a glimpse into my world.

Sometimes when I draw and I have no inspiration, I’ll look through my Instagram and find something I did years ago and maybe I’ll explore similar stuff and learn from my mistakes.

That’s how I try to treat Instagram.

It’s like, “this is my voice, this is my art journal”, and yes maybe public people can come and look at it and reach out to me, but it’s still me putting my piece out there in the void. Even if one or two people relate to it or maybe one piece gets through to a lot of people, you should never try to silence your creativity. No matter how small your voice is, at the end of the day you’re adding to this collage of different people’s perspectives, different viewpoints. I like that there is a page like mine out there, y'know it’s a half Asian, half European artist’s Instagram with weird drawings and shit, and it’s nice. When I make art, it’s my own understanding of my feelings and I shouldn’t be ashamed of it– it’s only going to help me grow. I keep my Instagram there because it’s my development, it’s my journey.

S: I think that’s an interesting way to put it, like fuck it if it goes into the void that’s the point. I do really like that approach. For me personally I find that comparison is the kind of death of my artwork.

P: Me too, I feel like that ALL the time. Especially with people younger than me who are 18 or 19 and already prodigies out there and you’re just like “wow”.

S: I also felt more like a user than an actual contributor to the void. I felt like the majority of the time I found myself scrolling scrolling scrolling and getting really depressed because I would find these great pages and instead of thinking, “it’s great work, my work can exist near it as well”, I was kind of like, “well, I’m irrelevant”.

P: Is that kind of like an impostor syndrome?

S: Probably, but I think in general what it comes down to is that it's built for keeping you on there to advertise to you – and happy people don’t do so well for buying stuff. And so I still continue to see it as you do and that’s what attracted me to doing it in the first place, and you put it better into words than I ever could, putting into the void. Because it’s you and you want to make stuff for the sake of making stuff and who cares what people are going to do with it.

P: Do you know what really helps me? I try to follow on Instagram a lot of accounts that are traditional, or old artists – like museum accounts, pages on romanticism, paintings, old illustrations, that means that my algorithm has new artists but also old artists because at the end of the day you can’t really try to compete with a legend who is also no longer here [laughs].

S: Well, my ego does! [laughs]

P: Yes, but they're great and they are famous. And it’s not like they have experience in the digital world of today.

S: I think in general what I’m trying to do is having it more as a business space because that’s what it kind of is for me at this stage. I even got to the point where I’d rather have someone managing it for me, because I just want to make the work – I don’t want to be endlessly looking at other people’s work.

P: Sometimes it makes you feel like you’re losing your path. I want to create A, but then you see a lot of Bs and Cs and you think “maybe I should try a bit of B, maybe a bit of C” and you almost start losing your intention.

S: I’m too insecure to be on the platform for too long [laughs].

As you can tell, our talking to Prawta is an informative rabbit hole of discussion. We most certainly didn’t expect to go down the topics of conversation that we did, but as we said, Prawta has an infectious personality filled with interesting, passionate ideas that anyone with a shred of curiosity would love to listen to. After conducting an interview like this you come away feeling extremely inspired and jumping to new ideas. We hope that one day Prawta will start a free flowing podcast so we can listen to her ideas more often.

If you liked Prawta’s words, be sure to follow her on her Instagram @atwar_pa. Her art perfectly reflects her words, and just goes to show what an uncompromising force of nature she is. We hope she continues to push her artwork out there and truly believe that she is designed to continue to create amazing things.